"Human language can repeat only an infinitesimal part of what exists."

-Mary Baker Eddy

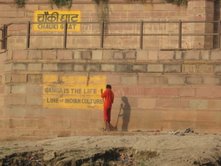

My trip to India marked a lot of firsts for me: first time I had to get a polio shot, first time anyone called me "ma'm," first time I ate lady fingers (and a lot of other things), first time I was told that I look Chinese, first time I wrapped a saree, first glimpse of the Himalayas, first time I feared monkeys...I could go on for hours. It was also the first time I'd ever kept a blog, but while my sporadic updates let my mother know I was still alive and saved us all from mass e-mail hell, I don't know if my words did this incredibly complex, eclectic, fascinating, frustrating, wonderful, chaotic country justice.

Right now I'm sitting at my parents' house in the guest room that has been converted into the holding cell for all my worldly possessions. I'm jetlagged and going through a bit of reverse culture shock, but it's good to be home. You just know when it's time for an experience to be over, when it's time to move forward and see how that experience has changed who you are, how you see the world and, possibly, the course of your life.

Lots of people asked me "Why India?" My stock answer was usually "why not," simply because I couldn't remember what inspired me to go to India. The more I researched and read about the country, the more my fascination grew to obsession with the Subcontinent-- its culture, its history, its religions, its politics, its problems, its contradictions. With each passing day, I somehow managed to simultaneously understand more and less about the country. There is no way to "sum up" a place like India in a neat, packaged description. It can only be experienced.

Why I chose India is no longer important. I'm just glad I did.